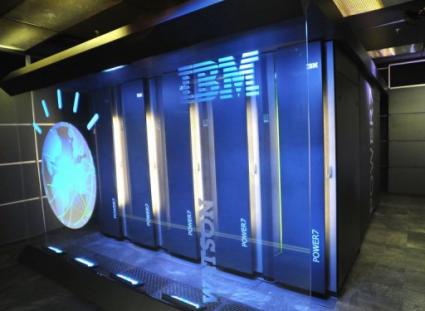

Watson, Creativity, and Jeopardy!

By Peter LloydEvery time a thinking machine pulls off a stunt like Watson’s victory over undefeated Jeopardy! champ Ken Jennings and top money-winner Brad Rutter, I feel it my duty to assure my readers that a machine will never perform a creative act. Watson will never present us with an invention, innovation, or even a child’s poem. The animal mind remains the unique seat of creativity.

In the latest IBM coup, sandwiched mercilessly within a three-night orgy of corporate chest pounding, Watson easily out-calculated two human brains. You may call the machine’s performance thinking but you may not call it creativity. Yes, Watson has come closer than Deep Blue to doing what we do when we doodle, laugh at a joke, or dream of being famous. But we will never catch Watson singing in the shower. We see primates, a few other mammals, and even birds behave creatively, but machines—never.

How Watson Works

When Watson considers a Jeopardy! question (actually an answer to which it must provide the question), its 2,500 parallel processor cores manipulate algorithms written by humans at about 33-billion operations a second. In mind-boggling time, Watson assigns a score to a host of possible responses. When it finds one or more that rise to a certain level of accuracy, it rings in and goes with the highest scoring response.

When Watson considers a Jeopardy! question (actually an answer to which it must provide the question), its 2,500 parallel processor cores manipulate algorithms written by humans at about 33-billion operations a second. In mind-boggling time, Watson assigns a score to a host of possible responses. When it finds one or more that rise to a certain level of accuracy, it rings in and goes with the highest scoring response.Richard Powers in What Is Artificial Intelligence? wonders “whether Watson is really answering questions at all or just noticing statistical correlations in vast amounts of data.”

I wonder, what’s the difference? When Jennings or Rutter responds, each puts to work some part of the 100-trillion neurological connections inside his three pounds of grey matter. How human brains do this remains a mystery, but the process may not be so different from Watson’s. After all, it was designed by the brains of David Ferrucci and his team. Would you be surprised if they have created Watson in their own image?

The IBM team evolved, if you will, Watson’s tremendous new power of open-domain question answering from Deep Blue’s relatively simpler mathematical manipulation of closed-set options. That’s a giant step for the field of artificial intelligence. Still, in the end, Watson simply does a lot more non-creative calculating a whole lot faster.

How Creativity Works

Our brains serve our human needs. Even when thinking giants like Jennings and Rutter engage in great feats of rational competition, they can only approach the dispassionate processing we see from Watson. The closer they get to Watson’s brand of pure, cold calculation, the better they do. Watson’s freedom from fear, pride, and the need to win is one of its greatest assets.

In contrast, driven by a need to perform, accomplish, and solve, Jennings, Rutter, and we lesser humans bring messy passion to the process. We think about how we think, care about what we do, and create what we desire. In this unique way, we are sloppier, error-prone, and singularly creative.

In contrast, driven by a need to perform, accomplish, and solve, Jennings, Rutter, and we lesser humans bring messy passion to the process. We think about how we think, care about what we do, and create what we desire. In this unique way, we are sloppier, error-prone, and singularly creative. Ironically, heeding our need for playfulness and fun helps quiet our fears, lifts our confidence, and allows our brain processes to flow. We do our creative best when we’re having fun. Our need for fun inspires games like Deep Blue vs. Gary Kasparov. Kasparov’s defeat represents a victory for human creativity. It drove the invention of Watson. An even greater human victory.

Questions

Feats of creativity (like Ferrucci’s, not Watson’s) raise more questions than answers. Now that we have Watson, what will we do with it? Watson obviously has the power to make Google searches many times more accurate and efficient. When will it power them? What else can it do for us? Lots of creative folks are working on these questions, I’m sure.

And I’m just as sure that neither Watson nor his progeny will ever answer the big ones. They may contribute to logical questions like: What’s the best exercise program for me? Should I see the doc about this discoloration on my ear lobe? But it will never touch questions that require creative thinking: Whom should I vote for? Does my lover really love me? Why is there something rather than nothing?

See also:

- Discuss this Workout on The Hub

- Opinionator: What Did Watson the Computer Do? by Stanley Fish, New York Times

- On ‘Jeopardy!’, Computer Win Is All but Trivial

- Progress in Artificial Intelligence Brings Wonders and Fears

- A Fight to Win the Future: Computers vs. Humans all above by John Markoff, New York Times, Science

- Quiz-playing computer system could revolutionize research by Nicola Jones, Nature News

- Machines beat us at our own game: What can we do? by Seth Borenstein and Jordan Robertson, Associated Press in PhysOrg

- New control system will allow satellites to 'think for themselves' by Ben Coxworth, Gizmag

Peter Lloyd is co-creator with Stephen Grossman of Animal Crackers, the breakthrough problem-solving tool designed to crack your toughest problems.