Not the Hammer’s Fault

Interview with Alan Iny, Co-author with Luc De Brabandere of Thinking in New Boxes, Part 1 “We believe the story of creativity is an epic of freedom. You have to be free in order to create, but you must first recognize you are a prisoner in order to break free.And this is true no matter how smart someone is, no matter how well run an organization is – we all become trapped by our boxes over time.” Thinking in New Boxes: A New Paradigm for Business Creativity, page 15

Vern Burkhart (VB): Congratulations on your book having made 800-CEO-READ’s Top 20 best-selling business books for 2013.

Alan Iny: It’s an honor and a delight. It’s quite exciting to be included among so many other great books, especially since our book was only released in September.

Alan Iny: It’s an honor and a delight. It’s quite exciting to be included among so many other great books, especially since our book was only released in September. VB: Your book has been published in English, French, and Japanese. Are there plans for translation into other languages as well?

Alan Iny: Translations are being done in Korean, Chinese, Italian, Spanish, Russian, and Dutch, and maybe more to come.

VB: I’m sure you’ve been in a whirlwind of promoting your book as well as continuing your consulting work with The Boston Consulting Group.

Alan Iny: You’re quite right. There’s been a mix of purely promotional activities like media conversations and, as you’d expect, meetings with BCG clients who are interested in talking about the concepts in the book. There’s been a global focus, which is a lot of fun.

There have been too many nights away from home, but I have been loving every moment of it.

VB: Why do you prefer to use the term ‘boxes’ rather than ‘mental models’?

Alan Iny: Both terms are useful, and are pretty much synonymous. We use the term ‘boxes’ because it is somewhat easier for people to visualize. Also, it fits with the ‘think outside the box’ paradigm that people have been talking about for decades.

VB: Why do you suppose ‘thinking outside the box’ has become so popular in innovation literature since it was first used in Aviation Week & Space Technology in 1975?

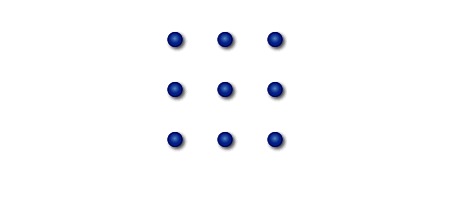

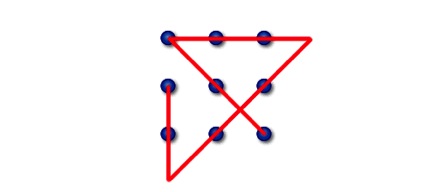

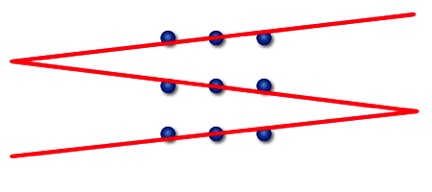

Alan Iny: The famous 9-dot puzzle to which it originally refers is a fun and evocative example of lateral thinking. From this perspective it’s a useful catch phrase.

The puzzle asks you to draw four straight lines, without lifting your pencil from the paper, so that they go through all nine dots. A variation is to link them with only three straight lines. It’s something your readers can look up if they’re not already familiar with it.

A statistician who died last year was aptly named George Box. He said, “No models are correct but some are useful.” Saying that the rainbow has seven colors isn’t necessarily more correct than saying six or eight, but it’s a useful simplification. In the same way the ‘thinking outside the box’ phrase has become popular because it’s useful and evocative.

VB: Whole books have been written about it.

Alan Iny: Quite right. Outside the Box, Inside the Box, and now, Thinking in New Boxes.

VB: When people are encouraged to ‘think outside the box’ does it do them a disservice?

Alan Iny: That’s a really interesting question. Thinking outside the box is necessary, but it’s not sufficient. It gives no practical direction for how to be creative.

It does do them a disservice in the sense that when people are told to ‘think outside the box’ seldom do they initially ask, ‘If I am supposed to think outside the box, what box am I currently in that I need to get out of?’ It most often leads to a random, unconstrained ‘blue-sky’ exercise with the result that even if the participants do break out of their existing mental rut they will veer off in random directions. The result will be the generation of ideas that have little chance of being useful and practical. They will be unlikely to address a specific well-defined question or problem, and they’ll be unlikely to end up with solutions that are practical to implement.

When somebody tells you to think outside the box it is like saying don’t drive on the highway. Your current boxes are not any good. It’s not giving you any direction about whether or not you should take the service road, take a train, or, instead, use a video conference. The key to finding a useful and creative new concept, pattern, working hypothesis, idea, theory, axiom, framework, or paradigm is to understand your current mental models or boxes and start to doubt and investigate them. If you can increase your awareness of the current boxes you’re using, then you can get outside of them in a thoughtful way and come up with new ideas.

For decades people have been saying that creativity is important – and it's true now more than ever – but a lot of people are frustrated when you say the word ‘brainstorm’ or ‘think outside the box’, because they’ve been involved in such sessions and they don’t always work.

VB: You say your advice to people who think brainstorming is painful and unproductive is like getting mad at the hammer when you hit your thumb.

Alan Iny: That’s exactly right. It’s not the hammer’s fault. It’s generally not the fault of brainstorming if you are unsuccessful while trying to have a brainstorm. We need to distinguish painful from unproductive. Brainstorming shouldn’t be painful but it does need to make you feel discomfort. It needs to challenge you by taking you out of your comfort zone.

If you do brainstorming right, then you can come up with some fantastically productive new boxes for whatever problem you may be facing. This requires you to build upon the principles that Osborn and others have laid out, update and tailor them to today’s business environment, and make them a bit more idiot-proof and easy to understand.

VB: You’re advising us to not criticize Osborn and reject the whole concept of brainstorming, but rather to properly focus the brainstorming exercise.

Alan Iny: Exactly right. As I said earlier, it’s like the hammer. When people get frustrated with the brainstorm the odds are high that they’re not doing it the way Osborn intended. We’re trying to help them do it in a way that will have productive results.

VB: One of the positive messages of your book is that we can learn to think in different ways. Does ensuring we do so require discipline and hard work?

Alan Iny: It absolutely does. People are wrong if they think they can achieve success by bringing a bunch of people together in a room with a flip chart and a plate of cookies, and brainstorm with no preparation or forethought. You can’t just tell them, “Ok everybody, let’s think outside the box.” You’re likely to fill many flip charts with ideas, but I don’t know that they’ll be very useful unless you happen to be lucky.

If you are thoughtful about preparing for your brainstorming session it does take discipline and hard work, but you’re much more likely to have useful outcomes. You need to understand your existing boxes. By this I mean you need to become conscious of the current assumptions you use to look at the world, the constraints under which you are operating, and the way your organization does things. If you take the time to focus on these items, think about a useful question, and identify some of the criteria of what would make for a good idea, then you will be better prepared to have a productive session.

VB: Discipline and hard work equal a higher payback.

Alan Iny: Quite right. It’s the case in most things.

Creativity also requires getting past your existing preconceptions and assumptions that color the way you look at the world and the way you do things. The biggest enemy of new boxes is our existing ones. Your outdated preconceptions may be so embedded in your thinking that you don’t even notice them. It takes an effort to recognize and overcome these preconceptions.

VB: ‘Thinking in new boxes’ suggests you should have a passion for change. Do you agree?

Alan Iny: It’s about recognizing that the world is always changing, and that change is unavoidable. No box is good forever. No good idea is good forever, whether it was the Model T Ford in the past or the iPhone today.

I wouldn’t say that a passion for change is required. As human beings we all love the status quo. We all love our routines and habits, and a feeling of stability.

Although a passion for change is always useful, it’s simply about recognizing that change is going to happen. You can either be proactive about coming up with a new box and strive to change the world around you, or you can be reactive with the result that at some point, you’ll have to play catch-up as others change things.

VB: In your book you say your five-step framework for thinking in new boxes builds on how the human mind thinks and reasons. What are some of the things about how the mind thinks and reasons that are key?

Alan Iny: The first important thing is to understand what a box or mental model is. You have to acknowledge that we all use boxes to think, and that we cannot avoid doing so.

When you see a couple walking down the street you make certain assumptions. Imagine it's a white haired man in his mid-fifties elegantly dressed in a suit, and a woman in her mid-twenties. When you see this image you can’t help but immediately come up with a box, with a mental model. Maybe you will think they’re two colleagues on their way to a meeting, maybe you will think they are husband and wife, or perhaps father and daughter.

All of us use these mental models to simplify the world in front of us. And we also need to recognize that we all get drawn into our existing models, which makes us subject to our cognitive biases. Cognitive biases have been explored in many other books. No matter how smart you are, you’re still a human being and all of those things do affect you. Understanding this is one of the useful elements for understanding how the mind thinks and reasons.

[Vern’s note: Authors Alan Iny and Luc de Brabandere’s five steps for creating and using boxes are doubt everything; probe the possible in order to ask the right question; diverge to create many new models, concepts, hypotheses, and ways of thinking; converge to select a smaller number of ideas; and reevaluate relentlessly in order to have a sustainable creative process that endures.]

VB: This says a lot about the unreliability of witnesses in court cases and trials.

Alan Iny: It does indeed.

VB: In your book you say, “…people use mental models or boxes within them (such as concepts and stereotypes) to handle the complex, continuously changing, often chaotic reality in front of them.” How does this work?

Alan Iny:

All day long we simplify the complex world in front of us, which includes society, our company, our customers, our family, other cultures, and more. We might see a rainbow and say it is composed of seven colors, which is a useful simplification of the infinitude of colors.

It’s the same with market segmentation. If you’re developing strategy for a company you may decide to target five, six, or seven market segments that represent 300 million of the potential 6 billion customers in the world. The idea is you develop these boxes – a strategy and a balance sheet are examples too – which are frozen for a period of time. This enables you to address the reality in front of you.

It’s like the older man and younger woman walking together. Maybe at first you think they’re colleagues, but then you see them holding hands so you decide they’re husband and wife. Then you hear her call him Daddy, and so you decide they’re father and daughter. We are constantly updating our boxes as we get new information from the world in front of us.

Think of the scientific process. We develop a box which is a working hypothesis. As we get more information our working hypothesis might change, and it often does change. Some of these boxes might last our entire lives, like our ideas about freedom and democracy, while others will be much more temporary like our view of the couple walking down the street.

VB: In your experience is there a danger that knowing there can be an infinite number of solutions to a problem can cause ‘analysis paralysis’ or difficulty in honing in on one solution?

Alan Iny: Yes, this is a potential problem for some people. Recognizing there is ambiguity in the world and that there may be an infinite number of solutions can indeed cause difficulty in drawing the issue to a conclusion.

However, it is still critical to embrace such ambiguity rather than fighting it, which so often is our natural tendency. If you ignore this ambiguity and think it’s black or it’s white, it’s this or that, then you are shutting down your openness to a large number of other possibilities. I’m claiming that you would be worse off by being closed minded than if you have to deal with the ambiguity which sometimes arises, even if it risks analysis paralysis.

VB: Is closed minded a polite way of describing ‘narrow minded’?

Alan Iny: I guess so. I know that some of those terms have negative connotations in terms of stereotypes, which isn’t what I mean to communicate. But it’s related, isn’t it?

Closed minded is a matter of not being open to new possibilities, new perspectives, and alternative points of view.

VB: “…no matter how smart someone is, no matter how well run an organization is – we all become trapped by our boxes over time.” Is this why it is so often difficult for businesses to change their business models?

Alan Iny: I think this is true. One of the reasons why it’s so difficult for businesses to change their business models is we have a natural tendency to become wedded to ‘the way we do things around here’. ‘This is the way it’s always been done’. ‘This is the way my predecessors did it’. No matter how good a manager or a leader you are, it’s a very human tendency to fall into these traps.

One of the thought exercises I often ask of my clients is to imagine what is the job of a CEO in a perfect organization where everything is running smoothly? People’s reactions often are that the CEO can relax, play golf, take extended lunches, spend more time walking about the organization, and similar activities. These type of activities may be possible due to the lack of immediate crises, but the job of the CEO is to figure out what the next big thing should be and when. What should be the new business model, new box, new product, or whatever other change should occur and the right timing for implementing it? In reality, of course, the CEO has help with this, but in a perfect organization where everything is running smoothly this should be the only task of the CEO.

VB: It would give the CEO more time to plan strategy.

Alan Iny: Quite right. If they’re willing and ready to take on the challenge.

VB: Would you talk about ‘Eureka!’ and how thinking in new boxes can help ensure that this experience happens to us?

Alan Iny: Since the world is always changing you have the choice of being proactive to come up with something new, or being reactive when other people come up with the next big idea and having to adapt to it. The whole point of a Eureka moment is being on the proactive side. It’s Netflix coming up with the idea of DVD’s by mail while Blockbuster was still dealing with bricks and mortar video stores. One person’s or company’s Eureka moment is a terrible ‘Caramba’ moment for the other side of the coin – for another person or company.

VB: Will reading and following the advice you provide in your book make businesses better able to prevent ‘Caramba’ from happening to them?

Alan Iny: Absolutely. The advice we provide in our book, and the idea of thinking in new boxes, is to push people in the direction of the proactive Eureka moment and further away from the reactive Caramba moment. Unfortunately, there’s no 100% guarantee!

Our advice is you should challenge your perspectives and be willing to look at things differently. You should try to think about the next big thing before it’s too late, and you should do this while the going is good rather than when you’re in crisis mode.

VB: Is ‘Caramba’ derived from the Spanish term ‘ai caramba’?

Alan Iny: Pretty much. The term came from my co-author, Luc De Brabandere. If you can imagine a 60 plus year old Belgian philosopher with a deep French accent describing a Eureka moment versus a Caramba moment, you will understand why we adopted this terminology!

You know him because in the past you interviewed him.

VB: Yes, we had an interesting conversation in September 2009 about his book, The Forgotten Half of Change, and IdeaConnection published two consecutive articles about his ideas. I recall him talking about there being two sides to change. In addition to the changing reality in the world there is the matter of change in the perception of people – how they look at the world. He pointed out that neglecting this ‘forgotten half of change’ is one of the causes so many mergers and change processes fail. This was highly valuable advice.

Alan Iny: Luc’s a fantastic character. He’s very different than me, and it is one of the reasons why it’s been such a great marriage for our co-authored book, Thinking in New Boxes.

VB: “…we would encourage you to always doubt…but never hesitate.” Would you talk about this?

Alan Iny: One of the things most people skip when they form a blue sky brainstorm session without any preparation is to always doubt. You may recall that earlier I said that lack of preparation is the reason so many brainstorms are unsuccessful.

One of the key elements of our advice, and a key suggestion for step one of the brainstorm process, is to foster doubt. It is to challenge your existing boxes before you try to come up with new ones.

If you were to take this to an extreme and merely encourage everybody to always doubt, then you would encourage second-guessing of everything. This would obviously not be a recipe for success or for good leadership; it would be a caricature of what a good manager should be. Always doubt but never hesitate means you need to always doubt your boxes and foster an environment where people are willing to challenge and look at them differently. But when it comes to a decision which needs to be made you should never hesitate. You need to be able to lead, to decide. If you know the machine is broken, then call somebody to fix it. If something is happening deal with it.

You need to be able to lead, to decide without second-guessing and hesitation, but you need to always doubt that what you’re proposing is the only possible way to go.

VB: Should following the 5-step process make it easier to make business decisions without hesitation?

Alan Iny: Yes, following the 5-step process does make it easier

The last step of the process is to always re-evaluate, to always pay attention to weak signals, and to recognize that the next Caramba moment might be just around the corner. You still need to foster doubt and be open to the next thing.

It’s a never-ending process even if it’s portrayed as being 5 steps. But, yes, it should help.

VB: Do you agree that accepting the principle of Occam’s razor can be risky for business success?

Alan Iny: There are many beautiful things about Occam’s razor. It’s the idea of going for the simplest possible solution. This is something the human mind does automatically. When we see an image in the world in front of us we jump to a conclusion, we come up with an idea. It’s an amazing aspect of being human.

It’s something that IBM and Google and others have tried to replicate. They’ve spent billions of dollars on chess and Jeopardy playing computers. Essentially they’re trying to imitate the inductive process of the human mind.

But sometimes this tendency to go for the simplest possible solution leads us astray. This is where cognitive biases come in. It’s why we have a tendency to jump to conclusions. If we see somebody and we know he has a Harvard degree versus being a college dropout, our mind will jump to conclusions that he will speak words of wisdom without any further information. Many times these conclusions will be correct, helpful, and useful, but sometimes they won’t. Sometimes we’ll be led astray.

This is another reason why it’s important to doubt. By all means take advantage of the human mind’s ability to jump to conclusions and go for the simplest possible solution, but remember that sometimes the mind will betray us. We have to be aware that this possible.

VB: We may reject the wisdom of the college dropout without actually listening.

Alan Iny: Exactly right, or we may overestimate the wisdom of the Harvard graduate.

VB: “As consultants, we’re particularly keen on helping people learn to detect those cognitive biases that are subconscious yet constantly shape your thinking, like the inexorable pull of a gravitational field.” Would you share a few tips on how we can learn to detect and overcome our cognitive biases?

Alan Iny: That’s a great question and a difficult one. Even Dan Ariely, Daniel Kahneman, and others who have written extensively about this question are subject to these cognitive biases, just like Luc, you, and me.

The best suggestion I have is to always ask questions. These can be questions like “Is this the only possible way to interpret the world in front of us? Am I framing this situation based on my particular way of looking at the world? Am I seeing this only through my own lenses? Are there alternative ways of looking at this?”

In the business world it might mean asking ourselves, “How can we redefine who our competitors are or what our business really is? How can we pay attention to some of the weak signals in the world in front of us? How can we identify some of the existing models that we use to look at the world in order to identify the constraints that are binding us?”

It’s about asking questions starting with, “Is this the only possible way to look at the world in front of us?”

VB: By having a doubting mind and by frequently asking this question it should help us overcome our cognitive bias.

Alan Iny: I think it will help us be more likely to overcome them. As long as we’re humans and not robots we will still have difficulty. It will always be a challenge and we will occasionally fail even with this approach, but it will help us be much more likely to overcome them.

VB: If you’re conscious of this risk, you should be in a better position to overcome cognitive bias.

Alan Iny: Absolutely. I’m with you.

VB: “You need to actively doubt the way you think about what could happen tomorrow, because the amount of chaos and uncertainty at play is (on average) more than you expect.” Is chaos and uncertainty ever increasing?

Alan Iny: I think it is. There’s quantitative data showing that the amount of volatility in every industry is increasing. By that I mean the number one, two, and three companies are switching places more often. The amount of uncertainty is increasing.

The world is changing faster than ever before. While it’s always been true that no idea is good forever, in the past if an idea had a lifespan of x now it’s probably 1/5th or 1/10th of x, depending on which industry you are in. Every industry is changing faster than ever before, and some are changing even more quickly, as is the case with technology and media. With more volatility and the shortening lifespan of a good idea, creativity in business is even more important.

VB: Does this suggest that the lifespan of an effective worker is probably reducing as well?

Alan Iny: That’s an interesting concept. One of the corollaries of this is people tend to change jobs more frequently than in the past when people would join a company at age 21 or less, and stay for their whole career. This change is likely also due to a lot of other trends in the world.

The lifespan of an effective worker is an interesting topic. If people are willing to constantly challenge their perspectives and look at things differently, maybe they could stay with the same organization. I haven’t thought enough about this point, but it’s a good question.

VB: When describing ‘probe the possible’, the second step toward thinking in new boxes, you say it ‘is not fundamentally about “understanding” but about seeking to understand’. Would you talk about this?

Alan Iny: When we say it’s fundamentally about seeking to understand rather than understanding we mean that we should maintain a spirit of doubt. In other words, if you have 200 pages of information about all the trends in your industry or you have a detailed customer research report based on hundreds of customer interviews, this is fantastically useful and necessary. But even in such cases there will be multiple ways of interpreting the data.

When you receive your latest monthly sales figures you could look at them in the same way as the last 12 months, or you could look at them with fresh eyes. Similarly, you could look at your trend data or customer research with fresh perspectives.

It’s about maintaining a spirit of doubt, and recognizing that there are a lot of different ways to interpret the wealth of information which we gather. It’s about seeking to understand in fresh ways.

VB: “…an important part of Step 2 [Probe the Possible] is realizing that your competitors may not be who you think they are, largely because the people and organizations most likely to come up with new ideas are often not those with the experience or the most obvious credentials.” Has this been the experience of most of your clients?

Alan Iny: It often takes an outsider to shake things up. This is where you see the stereotypical examples such as Hewlett and Packard working in their garage, and Zuckerberg in his dorm. There’s some merit to these anecdotal examples, because people from the outside are less bound to the status quo and ‘the way we do things around here’. However, I argue that it doesn’t have to be this way.

We try to get our clients, even the largest Fortune 500 companies, to refresh their perspectives. This means looking at things in fresh ways and trying to have Eureka moments before somebody in a dorm room or a garage has it before them.

When we think about competition in today’s world, the lines between industries’ various business models are blurring more quickly than ever before. The Marriott Hotel chain is no longer merely competing against Starwood and Hilton, but they’re also competing against Hotels.com. Watch companies are competing against computer companies. Nestle and Phillips are competing in the coffee business. There are all sorts of fresh ways in which industries being shaken up, and this is occurring more quickly than ever before. We bring this message to our clients: be willing to look at things in fresh ways.

Conclusion:

Don’t just try to ‘think outside the box’. We need to find new boxes for our thinking – new frames of reference. Consciously thinking in new boxes will better prepare us to make sense of the ever changing and sometimes chaotic world. It will enable us to better interpret, classify, categorize and make assumptions of the chaos and take decisive action.

Alan Iny’s Bio:

Alan Iny is the senior specialist for creativity and scenario planning at The Boston Consulting Group. He has trained thousands of executives and BCG consultants, runs a wide range of workshops across industries, and speaks around the world about coming up with product, service, and other ideas, developing a new strategic vision, and thinking creatively about the future.

Before joining BCG in 2003, he earned an MBA from Columbia Business School and honors BSc from McGill Univer¬sity in mathematics and management. Alan Iny lives in New York with his wife and daughter.

Alan Iny is the co-author with Luc de Brabandere of Thinking in New Boxes: A New Paradigm for Business Creativity (2013).