Quickening the Spirit of Invention

By Peter LloydContrary to conventional wisdom among creativity and innovation gurus, Alex Osborn is not the father of brainstorming. No surprise there, right? Conventional wisdom hardly ever proves itself wise. Which is why the wise rarely come up with anything conventional and jump up first to challenge anything that smacks of convention. Especially at creativity or innovation conventions!

To be fair, Alex Osborn did set down the basic concepts of brainstorming in the late 1930s. Since then they have evolved at the hands of many practitioners. These days you should take at least four principles into any brainstorming session:

To be fair, Alex Osborn did set down the basic concepts of brainstorming in the late 1930s. Since then they have evolved at the hands of many practitioners. These days you should take at least four principles into any brainstorming session:- There’s no such thing as a bad idea.

- The free expression of all ideas is encouraged.

- Seek quantity rather than quality of ideas.

- Encourage all of the above and build upon the ideas of everyone in the group.

Simple enough. But what’s so new about those principles? Don’t they sound like great guidelines for a Mardi Gras, rave dance, or office party? Nothing new at all. A spirit of idea liberation always precedes invention and innovation. Spontaneous, unstructured brainstorming shows up among children at play or a group of friends figuring out where to eat. Similar behavior must have sparked our earliest inventions—in your life and in human history. How else do we invent? How else do fresh, new ideas ever emerge?

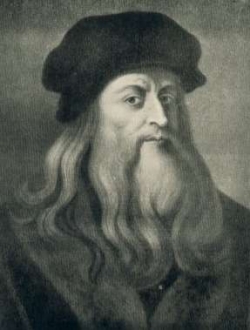

Michael J. Gelb, in his outstanding book How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci, quotes the master giving one of the earliest brainstorming guidelines on record. “A new and speculative idea, which although it may seem trivial and almost laughable, is nonetheless of great value in quickening the spirit of invention.” Sounds like principle number one to me. Principles two through four simply encourage more of it.

Michael J. Gelb, in his outstanding book How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci, quotes the master giving one of the earliest brainstorming guidelines on record. “A new and speculative idea, which although it may seem trivial and almost laughable, is nonetheless of great value in quickening the spirit of invention.” Sounds like principle number one to me. Principles two through four simply encourage more of it.When I lead brainstorming sessions an underlying agenda guides me. I want to transform what typically goes on among groups into behavior that one would find difficult to distinguish from play. In the best, most productive sessions, you see and hear a lot of what Leonardo would call “trivial and almost laughable.”

If that sounds too risky or risque for your aims, consider how soberly Stephen R. Grossman expresses the value of the laughable. In Transcendence as a Subset of Evolutionary Thinking: A Darwinian View of the Creative Experience he tells us how creative people in the arts and science experience a move toward a solution. At first, “their initial notion is often remote from the ultimate solution.” He’s talking about the kind of notions that make you think, “Are we on the same page?” Really great first notions make you wonder, “Are we on the same planet?”

Grossman writes, “The fact that an initial idea creates any sort of affective responses (excitement, curiosity, aesthetics) becomes a necessary primary motive to pursue it and see where it might lead.”

In my sessions, if anyone laughs at an idea, I usually direct the group to pursue it further. I’m guided by Leonardo and more recently by Albert Einstein, who has been quoted saying, “If an idea does not seem absurd at first, there is no hope for it.”

With or without the valuable work of Alex Osborn and solid advice from Steve, the other Al, and Leo, we all know how to brainstorm. The rules simply force us out of our habit of conventional thinking—a necessary coercion, which effective brainstorming can quicken.

Peter Lloyd is co-creator with Stephen Grossman of Animal Crackers, the breakthrough problem-solving tool designed to crack your toughest problems.